Theatre, Community, And Development:The Performance Activism Of The Castillo Theatre

The Drama Review (TDR), 60: 4 (T232) Winter 2016, Pp. 68-91

Dan Friedman

[+download]

Origins

The Castillo Theatre of New York City is named after the Guatemalan poet, theatre director, and revolutionary Otto René Castillo. He was exiled three times by the military dictatorship of his country. The third time he returned to Guatemala he joined the Guerrilla Army of the Poor, was captured by the government, tortured for three days, and then buried alive. That was in 1967. Three years later the first selection of his poetry was translated into English.

Those of us who founded the Castillo Theatre in 1983 fell in love with Castillo’s poetry. We were particularly moved by his poem “Apolitical Intellectuals,” in which he asks the apolitical intellectuals of his country, “What did you do when the poor suffered, when tenderness and life was burned out of them?” (Castillo 1971:17). As politically progressive intellectuals and artists living in the world’s wealthiest and most powerful nation—a nation characterized by a huge and continually growing gap in income and opportunity, with intractable poverty, particularly among African Americans —Castillo’s words resonated with us. Building the Castillo Theatre has been our response to Castillo’s question.

What the Castillo Theatre means by “building” is not simply putting on plays and getting people to see them; it’s organizing people who do not consider themselves actors or artists to participate in the creation of their own theatre and other forms of expressive culture. Culture, from our perspective, encompasses the many and varied ways we human beings have collectively organized how we see the world and ourselves in it. Reshaping/transforming culture is, Castillo believes, an integral part of any meaningful political and social change. At Castillo we see our mission as working to give people a chance to shape their own cultures from the bottom up, based on their own experiences, perspectives, and interests. Because culture is created collectively, transforming culture on a mass scale requires building community. The history of Castillo is at once the history of building a theatre and of building a community to support and constantly reshape that theatre.

The Castillo Theatre is part of a network of organizations and activities that have grown out of work that started in New York City’s poor communities of color in the 1970s. We who founded Castillo and its sister organizations started out as ideologically based (albeit unorthodox) Marxists. However, both our on-the-ground organizing experience and the collapse of ideologically determined revolutionary regimes around the world led us to embrace the notion, first articulated by Marx in his early writings, that “the changing of circumstances” and “selfchanging” are two aspects of the same activity (Marx [1845] 1970:121). Further, changing ourselves/changing the world, we have come to believe, is not primarily a cognitive-based activity; it requires all-around human development, and that, we believe, requires performance.

In 1998, the Castillo Theatre became a part of the All Stars Project, Inc. (ASP). ASP grew out of the All Stars Talent Show Network, an ongoing series of talent shows for young people in New York City’s poor neighborhoods initiated by the same circle of community organizers that generated the Castillo Theatre. Castillo and the ASP grew up side by side throughout the 1980s and ’90s. By becoming a part of the All Stars, Castillo formalized an existing relationship. Today the ASP is a national nonprofit organization active in six US cities with the mission of bringing the developmental power of performance to young people and poor communities. In addition to Castillo, the All Stars includes: Youth Onstage!, Castillo’s free performance school; the All Stars Talent Show Network, where young people produce and perform in hip-hop talent shows in their neighborhoods; the Development School for Youth, in which young people learn how to perform in the business world, partnering with business leaders who lead workshops and provide paid summer internships; Operation Conversation: Cops & Kids, which brings New York City police officers and young people of color together to play theatre games and do improv, and, in the process, create an environment for building new kinds of relationships; and UX, a free school of continuing development where adults of all ages, including teens, can attend classes, workshops, and cultural outings. (1)

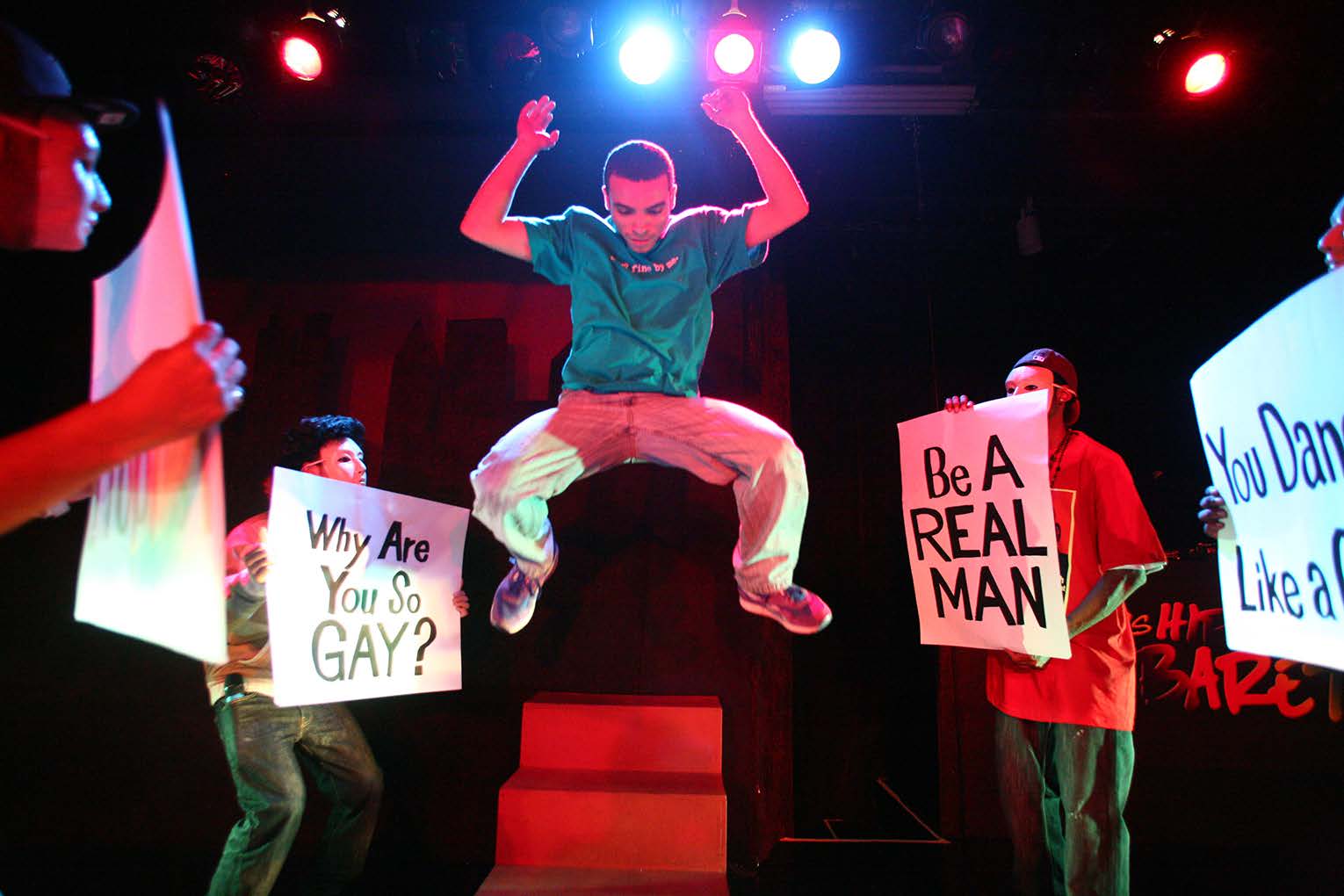

Jesse Vega (center) with ensemble in the All Stars Hip-Hop Cabaret #7, a devised production directed by Dan Friedman and Antoine Joyce at the Castillo Theatre, August 2009. (Photo by Ronald L. Glassman)

Dan Friedman is Artistic Director of the Castillo Theatre in New York City, which he helped to found in 1984. He is also Associate Dean of UX, a free community-based school of continuing development for people of all ages also in New York. He holds a PhD in theatre history from the University of Wisconsin, and has been active in political, experimental, and community-based theatre since 1969. dfriedman@allstars.org

Leading these decades of organizing was the late Fred Newman (1935–2011). Newman was originally trained as an analytical philosopher at Stanford University. He taught philosophy for six years at various colleges and universities across the country, and was fired repeatedly for giving all his students As. Newman left academia in 1968 (he was teaching at the City College of New York at the time) to spearhead the community organizing that eventually generated the organizations described above. Newman led the development of Castillo’s particular approach to theatre-making as community-building and served as the theatre’s artistic director and playwright-in-residence from 1989 to 2005. (2)

By unifying its theatre-making and community-building, Castillo Theatre has generated a performance-based approach to social development that we now call “performance activism.” Our understanding of the community we’re building is not static, that is, not defined by a particular geographic location, a particular ethnicity, or a particular professional category. It’s a dynamic understanding in which community comes into being and people are connected to each other through the very activity of creating the community.

Given that I lived through and participated in shaping much of what I recount here, I make no claim to either academic or journalistic objectivity. It might be best to approach what follows as simply a personal memoir of a collective experiment in a performative approach to social change. Whatever lens is used to read this essay, I write it with the hope that it’s of some value to those interested in performance studies, performance art, community organizing, and social activism.

Wither Castillo? 1983

Castillo’s earliest years were characterized by passionate disagreements among its founders about the shape the theatre should take. We were a diverse group of (at the very beginning) 12 artists who came out of the broad-based left cultural movement of the 1960s and ’70s that had fallen apart by the early ’80s. We were attracted to the political organizing being led by Fred Newman because we saw it as attempting to connect social change activism to the subjectivity (emotionality and ways of seeing) of the mass. Beyond that, we had little in common. Some of us came out of street theatre and agit-prop. I, for example, had spent two years (1969– 70) with the New York City Street Theatre Caravan and, while working on my doctorate on the Prolet-Bühne, America’s first agit-prop troupe, at the University of Wisconsin, cofounded Madison Theatre in the Park with fellow grad student Bruce McConachie. Upon my return to New York City in 1979, I founded and led Workers Stage, which worked with trade unions devising plays with union members involved in organizing drives and strikes. Another Castillo founder, Eva Brenner (from Vienna, Austria) had worked professionally with Heiner Müller and other cutting-edge theatre artists in Europe. She regarded the American agit-prop tradition I came out of to be crude and lacking in artistry. Castillo’s early builders also included a writer with something of a black nationalist politic, a feminist stand-up comic, two painters, two modern dancers, and one classical flutist. In its earliest manifestation, we called ourselves the Otto René Castillo Center for Working-Class Culture and, in addition to theatre performances, we produced regular gallery shows and occasional music and dance concerts, including New York’s first all-city breakdance competition.

These differences between Castillo’s founders resulted in more arguing than producing, until, after about a year and a half, we shifted from “epistemic debating” to “practical-critical” debating (Holzman 2000:86). That is, instead of trying to convince each other of “the correct” way forward we began creating productions that reflected our histories and perspectives. We divided into five creative teams, each responsible for devising (or writing) and producing one show a season. In 1986, Eva Brenner created A Storm Blowing from Paradise (The Decadence Show), a montage of European theatre texts inspired by Walter Benjamin’s description of Klee’s drawing of the Angel of History. The differences among us were revealed in two other productions that year. William Pleasant created The Anti-Black History Month Show, an interactive art installation that an accompanying leaflet declared was “against the corporate appropriation of Black History Month and for Black Liberation Everyday!” (Artists Committee 1986). I led the devising of All My Cadre, a soap opera about a group of young and restless political activists in New York City. We slowly began to influence each other and to discover what work most engaged our audience, which in those earliest days consisted primarily of other political activists and the people they were organizing in the city’s poor communities.

In those early years, Castillo also offered its space to other politically engaged and experimental performance artists, comedians, and theatre groups, working out box office splits on a case-by-case basis. Among those who graced Castillo’s first stage in the 1980s, a loft space on 20th Street just off Broadway in Manhattan: solo artists/storytellers John Patterson and Folami Adefumi; feminist comediennes Danita Vance and Reno; drag performer Alexis Del Lago; as well as performances by the Labor Theatre, the lesbian-feminist group Split Britches, the indigenous women’s performance troupe Spiderwoman Theater, and the Mime Rhythms of the Caribbean, a troupe touring from Cuba.

In 1986, Castillo asked Fred Newman to direct a play. He protested that he didn’t know how to direct a play. He did, however, know how to organize a demonstration. With the help of his Castillo colleagues, Newman created a performance piece that was a hybrid of the two. It was called Demonstration: The Uncommon Lives of Common Women. It started with two groups of women demonstrators: African American welfare activists and (mostly white) radical lesbian feminists. They met at a “street corner” set up in the middle of the loft, where performers and audience members milled about together. The staged confrontation of the demonstrators spun off into a montage of scenes, songs, video clips, and poems that traced the history of America’s progressive mass movements for social change since the late 1960s. The most significant thing about Demonstration was that the women performing were not actors; they actually were welfare rights activists and radical lesbians involved in the political organizing of which Castillo and its sister organizations were a part. Newman’s objective, reflected in this and subsequent plays, was to bring together communities pitted against each other due to legislation and funding practices organized around identity politics. This is the political/historical context in which Demonstration was created. Tension between welfare advocates and radical lesbians were real issues in the real organizing going on in the real world. Demonstration set two precedents: first, it established the practice of bringing formally trained actors and community people together onstage, which remains to this day; second, it started Newman writing plays —some philosophical, some topical, some both, and all political (with a small “p”) —44 scripts over the next 16 years.

From 1983 to 1989 Castillo’s activities were made possible by the New York Institute for Social Therapy and Research (the Institute), now the East Side Institute for Group and Short Term Psychotherapy (ESI), which provided Castillo, rent free, with a large room for rehearsals and performances in its 10th-floor loft space. In fact, the Otto René Castillo Center for Working-Class Culture started out as a project of the Institute. The Institute was founded in 1978 by Newman and Lois Holzman, then a postdoctoral researcher with Rockefeller University’s Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition. Over the decades, it has served as a research and training center and has spun off, in addition to Castillo, the Social Therapy Group, which utilizes the nontraditional therapy developed by Newman; and Performance of a Lifetime, a for-profit management consulting firm that brings improv and performance into corporate and organization management (Salit 2016).

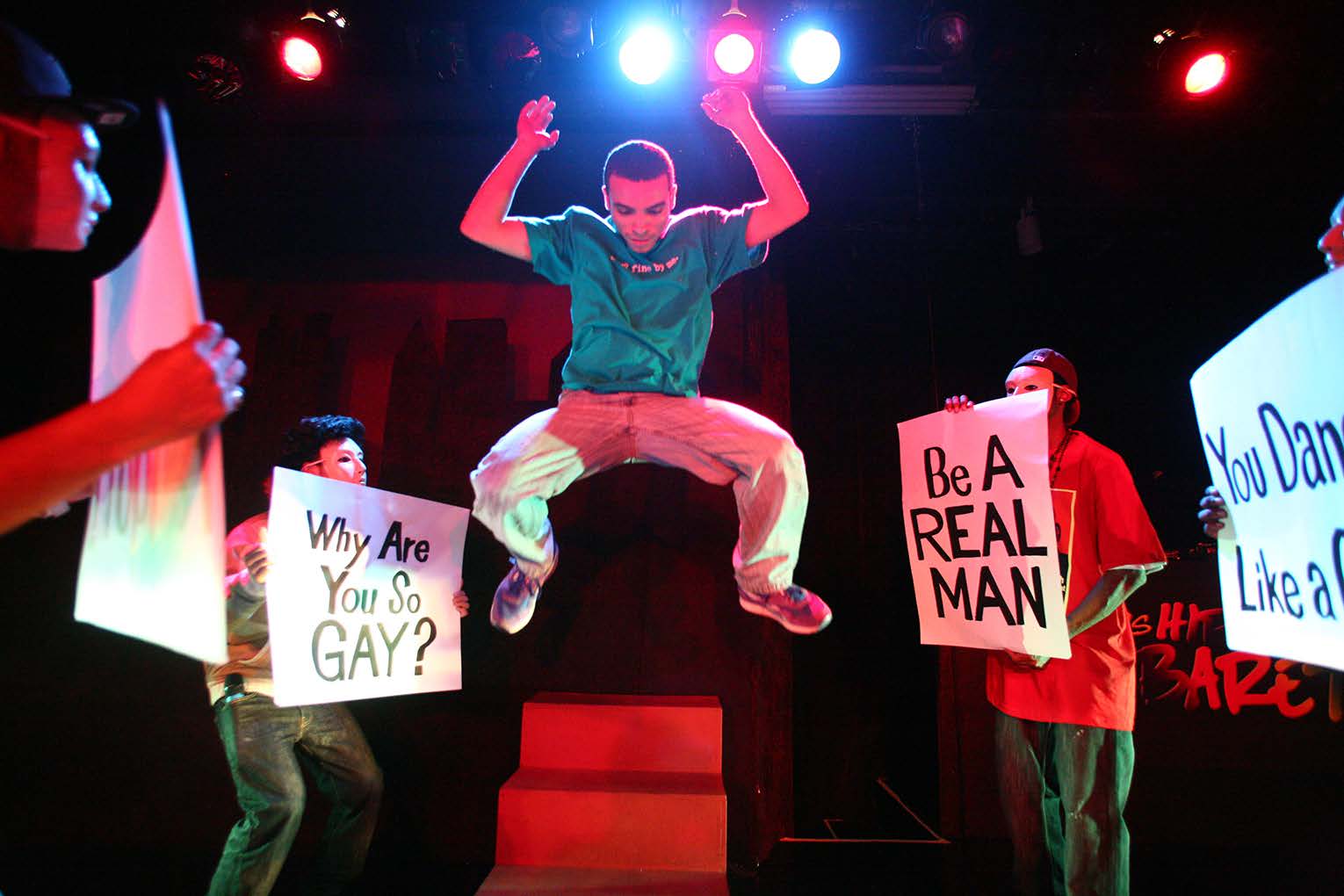

Molly Honingsfeld (left) and Jamela Stevens (right) in a Castillo fundraising street performance on the streets of New York City,1992. (Photo by David Nackman)

Castillo’s next step came with the help of Judy Penzer, a painter and founder of Castillo from a family of commercial real estate owners. She helped Castillo and the Institute purchase a larger loft space on Greenwich Street in west Soho in downtown Manhattan. But now Castillo had to help pay the mortgage—and therefore our community outreach and fundraising began in earnest. Faced with regular bills to pay, we did what community organizers do; we went to the streets and began talking to people, telling them about building an independent, politically engaged theatre, inviting them to shows, and asking them for money to support Castillo and/ or the Talent Show Network, our two projects at the time.

This was and is a political/ philosophical choice. Castillo began during the Reagan years when government funding for the arts in the United States, particularly for community-based arts groups, was being slashed. A number of progressive theatres, such as New York’s Labor Theatre, went under because they depended on government funding (and generously donated their lighting equipment to Castillo). We didn’t want to be subject to the will of City Hall, Albany

(New York State’s capital), or Washington, DC. The other side of this political/philosophical choice is that we didn’t just want to make theatre for the people, but with the people. We wanted theatre as a part of our community organizing, but we didn’t yet know if the community wanted theatre.

The street operation—which eventually grew to include door-to-door canvassing —was up and running seven days a week. All Castillo activists at the time were volunteers and the street organizing was done in the evenings after paying jobs and on weekends. We set ourselves quotas. Castillo needed a certain amount of money to pay the mortgage and produce the season. So if we didn’t, for example, make the goal set for a particular Saturday in 8 hours, we stayed out 10 or 12—whatever it took.Thus we began to win over people of diverse cultural and economic backgrounds to make financial contributions and to come to see our politically engaged plays, activities that many would never have dreamed of doing if we hadn’t reached out to them as part of our efforts to bring into existence a community-funded political theatre.

Everyone involved with building Castillo during much of the 1990s—actors, directors, designers, playwrights, producers, and community participants —joined in this street outreach. It was demanding and time-consuming. There were those in the Castillo collective who were conflicted or who openly resisted doing the street organizing. Their position, in effect: “As a political artist, I, of course, support our independence. And I agree we shouldn’t take government or corporate money. But I’m a director, not a fundraiser. You raise the money and I’ll direct the plays.” There were intense disagreements about this and some of Castillo’s founders and early builders left the group rather than fundraise on the street. In retrospect, the remarkable thing is that more people joined than departed. Some of the new people were folks we met on the street, and some of them were people who came to see Castillo’s shows and then asked how they might help in addition to giving money or buying a ticket. Castillo’s handful of organizers grew by the mid-1990s to scores of people deployed to the streets on a regular basis.

At the height of this operation, in 1994, we were canvassing and doing street outreach 7 days a week with approximately 30 people doing 12 hours a week each and another 15 people doing street outreach 4 to 12 hours a week. In addition, we had some 15 people each doing 24 hours of follow-up phone conversations (and some cold calling) every week. According to Bonny Gildin, fundraising director of the All Stars Project of New Jersey and vice president of Afterschool Development Research and Policy, ASP, Inc., through the totality of these efforts, that year we raised $1,300,024 from approximately 98,000 people (Gildin 2016).

In addition to laying the foundation for Castillo’s financial independence and building an audience drawn from diverse communities and social strata, this street work provided us, through practice, with a particular participatory approach to community building and theatre making. We found (and obviously we were not the first to discover this) that when people donate their money and/or their time to creating something, in this case a theatre, they have a very different relationship to it than when they simply buy a ticket. The performance ceases to be primarily an alienated commodity that entertains you in exchange for your money; it becomes a part of the coming-into-being of the community’s social and communal life. It is the social activity and the ritualized space, if you will, through which the values of the community can be publically demonstrated, its most difficult questions asked, and its most radical ideas explored. Although we were not, at first, fully aware of what we were doing, we built the Castillo Theatre and the community that sustained it simultaneously.

A Community of Givers and Performers

As those of us building Castillo and the All Stars Talent Show expanded our street fundraising to more affluent neighborhoods we quickly discovered that there were wealthy people who were concerned with the country’s growing gap in income and opportunity and with the ongoing impoverishment of the black community. These people were willing to donate money to cultural organizations that were working in and for poor communities. The talent shows, which gave inner-city youth a way to do something positive with their energy and skills, held particular appeal to many of the wealthier donors.These donors —mostly business professionals—introduced us to their friends and contacts and taught us how to organize traditional fundraising events like luncheons and galas. With the support of a donor in the fashion industry who we had met on the street, we held our first gala in 1998 at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall and raised $480,000.

By the beginning of the 21st century, the ASP (at that point consisting of the Castillo Theatre, the All Stars Talent Show Network, and the Development School for Youth) had grown from a street-funded local operation to a national organization with an actively engaged donor base that included elements of the business community, some of whom also volunteered with various programs and actively organized others to give and get involved as volunteers. The efficacy of this transformation can be seen in, among other things, the rise in ASP revenue from a smidgen over a million raised in small donations from 98,000 people in 1994 to $4 million in 2000 raised primarily from a few hundred affluent people.

In 2015, the last year for which figures are available, the ASP raised $10.3 million. Castillo’s revenue that year was $305,000, about 20 percent of which was earned through ticket sales. Other theatre revenue sources were the Castillo Gala ($55,000) and the Otto René Castillo Awards for Political Theatre ($30,000). Tickets to these events range from $175 to $1,500. The rest is raised through phone calls to people who have come to Castillo plays. There are currently 696 active donors to Castillo. The average donation in 2015 was $322. Castillo’s expense budget in 2015 was $874,160. The $569,160 gap between revenue and expenses was, as it has been since the late 1990s, bridged by the ASP. Thus, Castillo’s association with the ASP’s youth programs and UX has not only contributed to the creation of an environment in which the theatre could build a community and an audience, but gave it the financial wherewithal to survive and expand its production work.

The All Stars Project’s giving model might best be called participatory philanthropy, because we work to involve donors in the life of the organizations they are donating to. The clearest example of this is the Development School for Youth (DSY), which we launched in 1997. In the DSY young people from poor communities participate in weekly workshops with business executives who volunteer their time and expertise. If the young people stick with the DSY for a semester, they are guaranteed paid summer internships in these same companies. The first semester there were 17 DSY graduates placed in internships in New York City; in 2016 there will be 800 in six cities. The thinking behind the creation of the Development School for Youth is summarized by ASP cofounder Lenora Fulani, a developmental psychologist and community activist who, along with Pam Lewis, a Castillo actress who is now the ASP’s vice president of youth programs, founded DSY: “What we decided would be most helpful to the kids was to help them to become more cosmopolitan and we felt that these professionals were in a great place to help this to happen. It provided a means of giving the newly organized wealthy donors a way to give more than money. It provided them with an environment in which they could give their knowledge, their social location, their privilege to the young people —and themselves develop in the process” (Fulani 2013).

Reynaldo Piniella and Christine Komei Luo in Coming of Age in Korea, book and lyrics by Fred Newman, music by Anne Roboff, directed by Gabrielle L. Kurlander and Desmond Richardson at the Castillo Theatre, January 2009. (Photo by Diane Stiles)

As we were developing our street outreach and fundraising operation and evolved our participatory approach to philanthropy, we were also producing a lot of theatre. It was Newman’s most prolific period as a playwright and director. Between 1986 and 2009, Newman wrote 44 dramas and musicals, the bulk of them in the 1990s, and all of which he directed at Castillo. Many of Newman’s plays looked at issues and conflicts within the community that was coming into being and in the larger world of which it was a part. For example, in 1993 Newman and composer Annie Roboff wrote Still on the Corner, about the interactions of New York’s homeless poor with the middle-class folks who lived in apartments all around them. The issue of homelessness in New York and America has grown worse since 1993 and Castillo has revived the play several times, most recently in 2014. Another example: In 2002, shortly after the World Trade Center towers were attacked and destroyed, Newman wrote Sessions with Jesus in which Jesus Christ returns to New York City’s Upper West Side seeking a therapist. Why? Because Jesus is supposed to be all about forgiveness, but he’s having a very hard time forgiving Osama bin Laden —an emotional, ethical, and political dilemma that many in the United States and the rest of the world were struggling with.

Another important group of Newman plays challenged the identity politics that dominated left-wing thought in the United States from the 1970s through (at least) the ’90s. Newman, as a progressive political organizer, felt that identity politics held back oppressed people by pitting various communities against each other. Among his plays that address/challenge identity politics are: Mr. Hirsh Died Yesterday (1986); Outing Wittgenstein (1995); What Is to Be Dead? (Philosophical Scenes) (1996); and Crown Heights (with Friedman) (1998). Beyond the practical political implications of identity, Newman, in these plays, challenges the assumptions of essentialism. In Outing Wittgenstein, the title character, an alien visiting Earth from the planet Wittgenstein, tells some joggers he meets in New York’s Central Park that on his planet no one has an identity, “Identity is such a vulgar Earth-like idea,” he says. That sets off the following exchange:

EDDIE: No one has any identity? I mean...uh...how do you know who anyone is?

WITTGENSTEIN: Well, presumably our so-called identities are based on who we are. So we must have the capacity to know who we are logically and historically prior to having identities. It’s like any code. You need to know what something means before you encode it. Now some codes have positive value. Identity —human identity, Earthling identity—has none.

DIANE: So then, Mr. Wittgenstein, I wouldn’t be Black?

WITTGENSTEIN: Well, you are Black. You simply wouldn’t be identified as Black.

ALAN: It’s kinda like everyone is the same.

WITTGENSTEIN: Oh no, dear boy. It’s rather like everyone’s different. It’s those categories of identity that make everyone the same. (Newman 1998a:309–10)

During this period, Newman also wrote a series of “therapy plays” for performance at the annual conference of the American Psychological Association (APA). These short, whimsical fantasies critique the (often unspoken) assumptions of psychology as an academic discipline and as a practice and explore the philosophical underpinnings of social therapy. Most of Newman’s therapy plays feature characters drawn from modern history, including: the psychologists Lev Vygotsky, Jean Piaget, and Sigmund Freud; the writer Franz Kafka; and the revolutionaries Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and Leon Trotsky. Those staged at APA conventions included: Beyond the Pale (1996); Life Upon the Wicked Stage (1997); The Story of Truth (1998); Diary of a Mad Therapist (1999); and Odd Couple Seeks Professional Help: Marx and Messiah in Therapy (2003).

In 1998, Castillo published 18 of Newman’s scripts in a single volume, Still onf(4) the Corner and Other Postmodern Political Plays by Fred Newman (Newman 1998b). Gabrielle Kurlander, the president and CEO of the All Stars, who has been an actress and director with Castillo since the late 1980s, has expressed the importance of Newman’s plays to Castillo:

Newman’s plays give voice to what we care about, what we think is important, our take on history, and so on. We have a strong point of view and in the theatre we can give expression to that in a way that is not ideological, not truth referential, and is intellectually and politically stimulating. (Kurlander 2013)

Newman’s scripts remain a part of Castillo’s repertory; since his death in 2011, Castillo has included a full production of a Newman play each season, and every June around his birthday we hold “Performing Fred Newman,” a tribute marathon reading of his scripts organized by various directors.

In the ’90s Castillo also regularly produced new and/or neglected plays by African American playwrights including: Maisha Baron, William Electric Black, Ed Bullins, James Chapman, Nora Cole, Vernelle Edwards, Laurence Holder, and Robert Lanierbin. In addition, during this period Castillo produced a handful of progressive classics from the international repertory: Aimé Césaire’s A Season in the Congo (1995); Bertolt Brecht’s The Life of Galileo (1996); and Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade (2000); along with two plays by progressive Israeli playwright Yosef Mundy, It’s Going Around (1993) and The Governor of Jericho (1994).

However, other than Newman, the playwright most produced by Castillo in the 1990s (and beyond) was Heiner Müller. With 16 Müller productions between 1987 and 2010, Castillo has produced more Müller than any other American theatre. (3) Cofounder Eva Brenner introduced Castillo to Müller’s work, and to Müller in person when he visited Castillo in 1989 and had a two-hour conversation with Newman and some of Castillo’s founders. (4) Initially, there were those among us who didn’t see the value in producing Müller’s very dense, very Germanic postdramatic work for our mostly (at that time) working-class American audience. Newman, however, supported producing Müller, arguing that people —in this case both our actors and our audiences—develop by being challenged, by being asked to stretch, whether that be in politics, in the classroom, or in the theatre.

At the same time, we all were well aware of how strange Müller was in our social and cultural context. We worked with each production to build bridges between the text and our community. For example, in our very first Müller production, Explosion of a Memory/Description of a Picture (1987), audience members were encouraged to leave the performance at anytime, go to the lobby, which had been set up as an artist’s studio, or to another room in the facility that had been set up as a classroom and paint pictures or write poems or essays in response to the performance. They could return at any time to the theatre.

Castillo’s second production of Explosion of a Memory (1992) was a seven-hour event. It began with a modern dance troupe, Amy Pivar Dance, improvising to a projected video of Müller reading the text in English from the roof of the Berliner Ensemble. (He made the video for the production at our request.) Then the dancers, other performers working with Castillo, and the educators and social therapists who had been invited to participate in the event, along with the audience, all moved to the theatre’s lobby. There they talked about the play and the issues and questions it raised for them, improvised scenes based on these conversations, drew pictures inspired by its images, created and sang songs with lines drawn from the text, learned moves from the dancers, etc. After hours of such playing, they went out together, in groups, to dinner at various restaurants. After eating, everyone reassembled at Castillo and the dancers, utilizing the day of conversation and play, created a new version of their performance.

In the lead-up to Castillo’s all-female production of Müller’s Hamletmachine (1996) we organized workshops at which audience members played with the text; for the musical version of Hamletmachine (2002) we organized 25 readings of the text in peoples’ homes where friends and family could discuss the play. For some Müller productions, Newman, working with various musical collaborators, wrote songs, often performed with dance, which either unpacked or commented on the original texts. For Castillo’s second production of The Task (1994) Newman wrote eight songs, including one in which, with the collapse of their revolutionary mission, the main characters ask, in song: “What was our mission? / What was our task? / What was to be done? / What ever happened? / Don’t ask! / But it wasn’t very much fun. / Who would imagine / That millions would die / In the name of a stupid ideal? / Who would expect / That billions would cry / When they realized that nothing was real?” (Newman 1994).

Castillo actress Vicky Wallace (center) with Castillo volunteers at a “Camp Hamletmachine” workshop; one of a series of workshops at which Castillo volunteers and audience members played with the text of Hamletmachine by Heiner Müller, in preparation for its production at the Castillo Theatre, directed by Eva Brenner, June 2009. (Photo by Diane Stiles)

A Community of Volunteers and Artists

The three-way alliance the All Stars Project built between wealthy individuals, progressive artists-activists, and financially disadvantaged community members made it possible, between 1997 and 2014, for the ASP to expand to six cities and enabled scores of experienced organizers to leave their long hours on the streets and, instead, devote themselves to the development and deepening of the All Stars programs —including the Castillo Theatre and the launching of Youth Onstage!

The steadily rising amount of money donated to the All Stars Project allowed it to move in October 2003 to West 42nd Street between 10th and 11th Avenues. For Castillo this move meant a giant step from its small performance space on Greenwich Street to the ASP’s 31,000-square-foot facility on 42nd Street with three theatres (the Castillo, 90 seats; the Grunebaum, 104 seats; and the Demonstration Room, a flexible space that can accommodate up to 150 seats), two rehearsal rooms, dressing rooms, and set and costume shops. The building cost $7,750,000; purchase-related costs (mostly attorneys) $1,434,000; renovations of the building, $1,940,000; furniture, fixtures, and equipment $580,000.

Castillo’s location just at the edge of the city’s commercial theatre district has also allowed for a substantial expansion of the size and diversity of Castillo’s audience and volunteer base. As discussed above, in the beginning Castillo consisted of a collective of political activists who did everything, from acting and directing to raising money and cleaning the toilets. Throughout the 1980s and ’90s as Castillo’s range of work and the size of its audiences increased, so did the number of volunteers who were helping with discreet tasks. Volunteerism ramped up rapidly when we moved to our current facility. During the first season in the new space we were performing in all three theatres and we needed the staff to produce it. Under the leadership of the late Gail Elberg, the All Stars set up its Talented Volunteers program. Talented Volunteers currently holds two to three introductory sessions for new volunteers per month. The volunteers come through the grassroots networks Castillo and the All Stars have built over the decades as well as from organizations such as the Volunteer Referral Center and the websites VolunteerMatch.org, Idealist.org, and NYC .gov. In 2015, the All Stars in New York was made possible by the work of 875 volunteers. Of these, approximately 200 worked with the Castillo Theatre, 85 to 100 active at any given time. They worked on the production team, the tech staff, as house managers and house staff, box office staff, in the costume and set shops, on the sales team, the outreach team (which does street outreach and makes phone calls), and the “Whatever It Takes” team, which does just that.

With the birth of Castillo’s youth theatre, which coincided with the move to 42nd Street, another kind of volunteer developed. Professional theatre people — actors, directors, and choreographers — asked to volunteer to teach classes and direct plays with Youth Onstage! In the ’90s, Castillo had produced two plays with youth from the All Stars Talent Show Network — Newman’s Carmen’s Community (1995) and Crown Heights, which I wrote with Newman (1998). After Castillo moved to 42nd Street, it was able to do more than one production at a time and to make use of its two rehearsal rooms for both rehearsals and classes. It also had the human resources to launch Youth Onstage! Castillo’s location within walking distance of Times Square, a major subway hub, made it easier for young people from all over the city to get to it and it also began to attract professional actors, who would walk into our street-level entrance and ask what and who had taken over the space.

At first we thought that Youth Onstage! would simply be a youth theatre. The first YO! production, which I directed in 2004, was a revival of Crown Heights, a musical “learning play” based on the 1991 riots between blacks and Hassidic Jews in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. As we worked to bring Crown Heights to fruition with a cast of 18 mostly untrained and inexperienced black, Jewish, and Latino teenagers, some of these theatre professionals offered to help out. One, a voice teacher at the Atlantic Theatre Company, became our voice coach and eventually played the one adult role in the play. Another actress, who had recently left the cast of Broadway’s Urinetown due to a knee injury, became our singing coach. A veteran of the Gotham City Improv Company did improvisation workshops with the cast.

In the course of our three-month workshop and rehearsal process, it became clear that there were theatre professionals who wanted to volunteer their skills to teach “underprivileged” young people and who were hungry for the socially committed mission of Youth Onstage! Even before the eight-week run of Crown Heights was over, I started organizing an intensive Summer Theatre Institute that brought together theatre pros and young people interested in the theatre for five hours a day, four days a week. Since then, Youth Onstage! has done three semesters per year (the summer remaining more intensive), offering free classes in voice, movement, improv, character development, singing, etc.

Antoine Joyce, performing as the MC with ensemble in the All Stars Hip-Hop Cabaret #1, a devised production directed by Joyce and Dan Friedman at the Castillo Theatre, March 2004. (Photo by Ronald L. Glassman)

Since its first semester of training in the summer of 2004, YO! has had 166 professionally trained theatre artists, mostly early career actors in their mid to late 20s, work as volunteer performance teachers. Of those, 15 went on to direct or codirect youth productions at Castillo. The Youth Onstage! faculty has included graduates of: the American Conservatory Theatre; American Repertory Theatre/Harvard; the Berklee College of Music; Julliard; the Neighborhood Playhouse; Pomona College; the conservatory program at Purchase College of the State University of New York; the New School; New York University, Tisch School of the Arts; Sarah Lawrence; and Yale.

Between 2004 and 2015 there were 28 Castillo youth play productions, along with 7 All Stars Hip-Hop Cabarets and 4 poetry snaps. While the predominate modality for developing Youth Onstage! shows has been devising, scripted youth productions have ranged from plays authored by everyone from Newman to Shakespeare to Aimé Césaire to Katori Hall. In addition, 12 scripts written by Youth Onstage! students who had participated in playwriting workshops with me have been produced at Castillo.

Devising has been the method of putting together our All Stars Hip-Hop Cabaret youth productions. Between 2004 and 2009 Castillo produced seven of these under the codirection of Antoine Joyce and myself. Joyce grew up in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn and first became involved with the All Stars Talent Show Network in 1991 at the age of 13. After years of performing and conducting outreach to communities and schools as a volunteer, Joyce joined the All Stars staff in 1997 and rose to the position of National Producer of the All Stars Talent Show Network. He was instrumental in developing new All Stars programs in Newark and San Francisco/Oakland and fostering the development of affiliates in Boston, Atlanta, and Los Angeles in the US, as well as in Amsterdam. (Along the way, Joyce founded a music management company that produced a 20-country tour for DJ Grandmaster Flash.) In the fall of 2013 he moved to Dallas, Texas, to found and lead the ASP there.

The Hip-Hop Cabarets brought together young rappers, singers, dancers, and spoken word artists from the All Stars Talent Show Network to create original political cabarets in the spirit of the German and Austrian political cabarets of the 1920s. These cabarets were created through conversation and improvisation around themes that concerned the young people who participated. Subjects ranged from sexism to the war in Iraq, from unemployment to conflict with the police, from homophobia to drug dealing and violent death. The young people created original raps, songs, dances, and skits that, with Joyce as the MC, were woven together by Joyce and me into an evening of political satire and entertainment.

Another way that devising has been used at Youth Onstage! is in the creation of plays that combine topical concerns with philosophical investigations. One example is The Work/Play in 2009. In the wake of the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009 following the collapse of the sub-prime housing market, jobs (or rather the scarcity of them) was a major concern and topic of conversation among the young people and their families in our community. We decided to create a play that looked at the relationship between work and play. We began the rehearsal process by showing a video interview with Fred Newman discussing the concepts of work and play over the centuries. The young actors then interviewed their parents and other relatives about their jobs (which included a barber, a security guard at a homeless shelter, a Verizon technician, a residential associate at a home for disabled children, and a public school teacher) and then shared those conversations with the ensemble. We discussed what work and play looked like in their schools and homes. The devising process included holding a number of panel conversations with workers from a wide range of jobs. Through all of this, the ensemble improvised, wrote, and tried out scenes, poems, and raps and, gradually, created a full-length play in which the allegorical sisters, characters named Work and Play, try to figure out how to have a healthy relationship.

Most recently, in 2015, under the direction of Craig Pattison, Youth Onstage! performers devised their own version of Antigone, in which various actors moved in and out of the roles of Antigone and Creon. Pattison was a professional actor in his mid-20s when he became a volunteer teacher with Youth Onstage! in 2007. When he met the All Stars he had worked at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival, the Denver Center Theater Company, the American Repertory Theatre, the Berkeley Repertory Theatre, the Roundhouse Theater, the Irish Repertory Theatre, and Theatre for a New Audience. In 2009 he became the program manager for Youth Onstage! and three years later he joined the professional fundraising team at ASP. Prior to Antigone, Craig had directed Castillo youth productions of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Julius Caesar. He also oversaw the six-play Young Playwrights at Castillo Festival, which featured the acting and writing talents of YO! alumni.

The Youth Onstage! Antigone retold the ancient story and, at the same time, was a critique of the play and the very concept of tragedy. The actors, as themselves, meditated on the notions of fate and destiny in relation to the poverty and lack of opportunity in their lives. Near the end of the performance one of the young performers set up a folding chair downstage center and addressed the audience directly:

So now you know the ending of Antigone —the famous important play. You heard about it as we played some great old school doo-wop just now. We can’t perform it for you. We don’t want to. Cause we don’t like it. We don’t like “too late.” Maybe we don’t like tragedy. We’ve got too much of it before we come here and after we leave here. Sure, you expose the problems of the world, but what about a play that offers an alternative to all this catharsis? Or deals with those who are left and how they work to make things better and not fall back into the same old fate wheel of bad destiny? (Pattison 2015:12–13)

This monologue segued into all the actors coming onstage and leading a discussion with the audience.

Since the turn of the century, in addition to its youth productions, Castillo, as noted above, has continued to produce plays by Newman and Müller. In 2009, Eva Brenner returned to Castillo to direct Hamletmachine. The following year, Gabrielle L. Kurlander directed The Task ( January 2010) and Playing With Heiner Müller (November 2010), a collage of his work, both with all black casts, thus putting to rest the charge that Müller appeals only to white avantgardists. The Task won the AUDELCO (5) Award for Best Ensemble Production in the Black Theatre. In 2013, Antoine Joyce, working with Madelyn Chapman, an actor and director who has been with Castillo from the start, restaged Explosion of a Memory/Description of a Picture. While not changing a word of the text, they created Hip-Hop Explosion, a totally hip-hop version of the play.

(From left) Shashorna Bailey, Nicosie Christophe, Kelechi Stuart, Monique Allen, Sierra Hamilton, Malique Richardson, JeWayen Thompson, Starshima Trent in Antigone, a devised play based on the script by Sophocles, directed by Craig Pattison at the Castillo Theatre, September 2015. (Photo by Ronald L. Glassman)

(From left) Lorenzo Jackson, Niara Nyabingi, Rain Jack, Kimarra Canonnier, Franceli Chapman, LaTonia Antoinette, Mariel Reyes, Starshima Trent, Andrea Rachel, Lauryn Simone Jones, and Edgar Cancinos in Katori Hall’s Children of Killers directed by Emily Mendelsohn at the Castillo Theatre, September 2012. (Photo by Ronald L. Glassman)

A Community of Collaborators

Castillo during this period has also hosted both full productions and staged readings of new political scripts by a variety of relatively unknown political playwrights, many of them winners of the Mario Fratti-Fred Newman Political Play Contest, launched by Castillo in 2007, which attracts about 200 entries each year.

The best-known new playwright produced by Castillo during this period is Katori Hall. Hall came to Castillo through Shawntane Bowen, a volunteer teacher with YO! who had been in the same class as Hall at the American Repertory Theatre. In 2010 Hall had been commissioned by the Connections program of the National Theatre in the UK to write a play for young people. Drawing on her experience in Rwanda the previous year when she had attended a genocide studies conference and had spoken with victims and perpetrators of the 1994 genocide, she drafted Children of Killers, a play about a group of Rwandan teenagers 15 years after the genocide, whose fathers, convicted of being mass murderers, were being released from prison and returning to their village. Hall and the National Theatre were looking for a place to workshop the play and originally had Julliard in mind. However after Bowen told Hall about Youth Onstage!, we met and she decided toworkshop it with YO! students. Anthony Banks from the National Theatre came to New York and did a week-long workshop of the script, which ended with a performance for an invited audience. Hall then revised the play and it went on to receive 8 youth productions in Britain and 40 in Portugal in 2011.

The next year, in September 2012, Children of Killers received its American premier at Castillo with a mixed cast of Youth Onstage! alumni and professionally trained young people. It was directed by Emily Mendelsohn, a young American director Hall met in Rwanda. In a rare review for Castillo, Charles Isherwood, in The New York Times, wrote,

Ms. Mendelsohn’s production, while rough-hewed and obviously produced on a small budget, gets the important things right: most of the performances are strong and individualized, the mood quietly unsettling. Small details can bring you up short: during a quiet scene at Vincent’s house, you suddenly notice the machetes carefully mounted on a shelf like family treasures. Vincent’s mother casually takes one down to use as a mirror, curious to see how she looks with the lipstick she has put on to welcome her long-absent husband. (2012:D6)

In 1999, four years before our move to 42nd Street, Castillo launched the Otto René Castillo Awards for Political Theatre. The idea was to honor others who were doing progressive political, experimental, and community-based theatre and performance. It seemed to us that they deserved recognition and it would be, we hoped, a way to help Castillo and other theatres get to know each other and network. The first year, we nominated artists and theatres we knew and had worked with in New York City. We then invited the first year’s awardees to be part of the nominating committee for the following year, with the committee expanding to include the new honorees each year. All past Otto winners are invited to make as many nominations as they want each year. The nominations are then voted on by the committee and those with the most votes are the next year’s winners. To date 104 theatres and theatre artists have been Otto awardees. Some of them are well known artists and theatres: Bread and Puppet Theater, Ed Bullins, Joseph Chaikin, El Teatro Campesino, Woodie King Jr., Judith Malina and the Living Theatre, Charles Mee, the Nuyorican Poets Café, San Francisco Mime Troupe, Richard Schechner, Ntozake Shange, SITI Company, Ellen Stewart, and Robert Wilson. Many more are little known outside their geographic areas and have labored for years and even decades in obscurity. In addition to the United States, winners have been based in Austria, Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, Jamaica, Japan, Northern Ireland, Pakistan, Serbia, and the United Kingdom. (6)

As Castillo prepared for its move to 42nd Street, Newman initiated Five Points Productions, a small partnership with community-based theatres and theatre artists in New York City with whom we had been friends over the years. The goal was to share our new theatre space. Five Points included: Woodie King Jr. and his New Federal Theatre; Carol Polcavar and her New Village Productions; Rome Neal of the Nuyorican Poets Café; and playwright Laurence Holder. In 2004, the first season that the All Stars was on 42nd Street, Five Points produced The Solution to All The World’s Problems: A Evening of Short Works for the Stage by Ben Caldwell, directed by Woodie King Jr.; and Sister Music, written and directed by Carol Polcavar, a farce set at an all-women’s musical festival crashed by rock musician in search of his bisexual wife.

Five Points evolved into a regular producing partnership with the New Federal Theatre (NFT). In 2007, NFT and Castillo coproduced Newman’s Satchel: A Requiem for Racism at the Abrons Art Center at the Henry Street Settlement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. From 2009 through 2015 NFT and Castillo brought to the stage 16 coproductions at Castillo (including two by Ed Bullins and two by Amiri Baraka). In addition, there have been three coproductions between Castillo and the National Black Touring Circuit.

(From left) Nicholas Jenkins, Shane Baker, and David Mandelbaum in the first-ever Yiddish language production of Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett, translated by Shane Baker and directed by Moshe Yassur. A coproduction of the New Yiddish Rep and Castillo Theatre, September 2013. (Photo by Ronald L. Glassman)

In 2013, Castillo coproduced, with the New Yiddish Repertory Theatre, the first-ever Yiddish production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, which was invited to the Happy Days Beckett Festival in Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, and upon its return to New York City had a successful commercial run at the Barrow Street Theatre. In 2015, New Yiddish Rep, in association with Castillo, produced Tout fun a Seylsan, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman in Yiddish. The production was nominated for a Drama Desk Award for Best Revival and Avi Hoffman, who played Willy Loman, was nominated for Best Actor. Also in 2015, the Caribbean Repertory Theatre, in association with Castillo, staged Athol Fugard’s Sizwe Bansi Is Dead.

Youth Onstage! has also sought out collaborations. With the all-girls viBe Theatre Experience, YO! did a joint devised production, Fine Print (2008) on gender roles. With a cast drawn from both groups, City Lights Youth Theatre and Youth Onstage! produced The Grapes of Wrath (2010), adapted by Frank Galati from the John Steinbeck novel. In 2015 Youth Onstage! held a joint workshop with young performers from the Rios de Encontro project of the Transformance Institute from Calbelo Seco, Brazil, a group led by Dan Baron-Cohen, and hosted a performance by the Brazilian youth of their devised dance drama, Let Our River Pass.

The expanding diversity of Castillo’s productions and coproductions has brought with it increasing audience diversity. The cultural backgrounds of Castillo’s audiences can vary depending on the production. For example, in 2015, Tout fun a Seylsan drew a primarily Jewish audience, while, at the same time in a theatre located on the other side of the All Star’s lobby, Martin Duberman’s In White America, coproduced with the New Federal Theatre, attracted a primarily black audience. These coproductions result in some crossover in audience attendance at each play and add to the Castillo Theatre’s audience pool. At its most diverse, a Castillo audience may include middle-class white theatregoers from New Jersey sitting next to a group of black church ladies from Brooklyn sitting next to some hip-hop youth from the Bronx sitting next to a gay couple from Chelsea sitting next to hedge fund executives from Connecticut. They are in those seats because Castillo builders have organized in all those communities and social strata.

Heather Niccollette Lewter and Anya Opshinsky in The Grapes of Wrath adaptation by Frank Galati from the novel by John Steinbeck, directed by Rob McIntosh. A joint production of Youth Onstage! and City Lights Youth Theatre at the Castillo Theatre, March 2010. (Photo by Ronald L. Glassman)

Castillo’s audience has increased in both diversity and size since moving to 42nd Street. The 2014/2015 season drew a total audience of 7,150 people. By contrast, the last season in our previous location on Greenwich Street (2002/2003) had an audience of 3,406. Since the move to 42nd Street (that is, from 2004 through 2015) a total of 84,430 people have attended Castillo productions and coproductions. Castillo ticket prices currently range between $15 and $35, with individual youth tickets at $10. There are group rates with ticket prices going down as the size of the group goes up. Typically about a third of the audience for a Castillo run comes through group sales. In addition, we hold two Pizza and a Play nights (one for youth program participants, the other for UX students) for each production. For these we host a pizza and soda reception before the show and provide free tickets to the performance. In this way, we assure that scores (sometimes hundreds) of those who can’t afford Castillo’s relatively modest ticket prices are part of the audience mix.

In 2008, the All Stars began cosponsoring and hosting Performing the World (PTW), an every-other-year interdisciplinary conference that brings together theatre people, community activists, youth workers, educators, researchers, therapists, health workers, and others who are using or researching the use of performance to impact social change and human development. The first PTW was organized in 2001 by the East Side Institute for Short Term Psychotherapy (ESI) and attended primarily by psychologists and educators interested in the interplay between performance and the arts with their practice and research. When the All Stars began cosponsoring the conference in 2008, PTW relocated from conference centers in the suburbs of New York City to the All Stars 42nd Street facility. This has allowed PTW to lower registration fees by hundreds of dollars. Castillo has played an active role in bringing theatre artists and applied theatre practitioners into the mix. Among them: Vojislav Arsic (Serbia); Andrew Burton and the Street Spirits Youth Theatre (British Columbia); Carlyle Brown; Chang Janaprakal Chandruang and his youth theatre, the Moradokmai Theatre Company (Thailand); Carol Dorfman and her dance company; Dzul Dance; Katori Hall; Woodie King Jr.; Sanjay Kumar (India); Judith Malina; Daniel Maposa (Zimbabwe); Charles Mee; Sahid Nadeem (Pakistan); Syed Rahman (Bangladesh); Richard Schechner; William Huizhu Sun (China); Chris Vine and Helen White from the City University of New York’s Creative Arts Team; and Carl Weber.

Except for a few technicians hired to help with the needs generated by up to 10 presentations happening at the same time, PTW is produced by volunteers. The last conference in 2014 was attended by 420 people from 32 countries and 20 states in the United States and made possible, over three days, by the work of 181 volunteers drawn from the All Stars and ESI’s community networks. In addition, volunteers in communities ranging from Harlem to the Upper East Side, from the East Village to Fort Greene and Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn have opened up their homes for free to PTW attendees who can’t afford the city’s high hotel costs. Since PTW moved to NYC, depending on the year, between 59 and 120 people have hosted attendees of PTW. Most of the visitors offered free housing have come from outside the United States. Thus the community of volunteers built by the All Stars not only makes Performing the World possible, but theatre artists, activists, researchers, and teachers from different parts of the world and “ordinary” people in New York get to know each other and, in some cases, form long-term friendships.

Yet another kind of collaboration initiated by the ASP and produced by Castillo is between active-duty New York City police officers and young people of color from poor communities. Operation Conversation: Cops & Kids brings officers and young people together in community centers, Police Athletic League centers, churches, libraries, and schools in working-class neighborhoods to play theatre games together and improvise skits. In the process they create an environment in which facilitators can then lead the cops and kids in an honest (often difficult and moving) conversation about their perceptions of each other. Lenora Fulani launched Operation Conversation in the wake of the police killing of Sean Bell in November 2006, as an attempt to use play and performance to change the culture of hate and mistrust between the police and the community.

Like most All Stars activities, Operation Conversation started at the grassroots level, with Fulani gathering together cops and kids she knew through the All Stars and her years of political activity in communities throughout the city. Doing about two workshops a month for the first few years, word spread through the police ranks and in 2012 the New York Police Department (NYPD) entered into a partnership with the ASP and Operation Conversation became an official part of the city’s police training. Since then, Fulani has trained three teams consisting of a social worker and a theatre artist to lead workshops and the number of community workshops has increased to three or four per month. Between 2006 and 2015 there have been 138 workshops (109 led by Fulani, 29 led by the newly trained facilitators) involving 1,386 cops and 1,697 kids.

In addition, the Castillo Theatre, working with Fulani, has produced public performances of the workshop—with actual kids and real cops who have previously participated in community workshops—for the graduating class of the police academy and people brought in by the All Stars from communities throughout New York City. These public demonstration workshops have taken place at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, the Christian Cultural Center in Flatlands, Brooklyn, and the last five times, at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. Between July 2012 and January 2016 there have been eight such public performances by 53 police officers and 53 young people, attended by 5,129 probationary police officers and 2,688 community members. In 2015 the International Association of Chiefs of Police awarded Operation Conversation: Cops & Kids the Cisco Community Policing Award

Operation Conversation: Cops & Kids demonstration workshop at the Apollo Theater, August 2014. (From left) Starshima Trent, Officer Michael Murdock, Akeil Davis, and Officer Victor Ramos. (Photo by Kenneth Pietrobono)

A Performance Community

While it’s been helpful to examine Castillo’s evolution through the lens of various overlapping community-building activities (a Community of Givers and Performers, a Community of Volunteers and Artists, a Community of Collaborators), it’s important, I think, to keep in mind that all these communities comprise one community. Producing plays, bringing together poor youth and business executives, housing international guests at a performance conference, having cops and kids do performance workshops—all of these activities are part of the ongoing attempt to generate a social environment in which performance can creatively engage the world as-it-is and people can gain a sense of themselves as creators and changers. To better understand how this happens, we need to dig deeper into Castillo’s understanding and practice of “performance” and “development” as they have emerged over the three decades of Castillo activity.

As discussed earlier, for a good part of the 1990s, Castillo and the All Stars Talent Show Network raised virtually all their funds on the streets of the city and by canvassing door-to-door, building our audience and our funding base conversation-by-conversation, dollar-by-dollar. Later, money also came in from well-off supporters in larger batches. Beyond maintaining our political and financial independence, the activity of raising money from individuals has been key both to building Castillo’s community and, as I will address here, to the emergence of performance activism as a means of social engagement and development.

What made it possible to sustain this intensely committed work was approaching fundraising—especially fundraising in the streets—as a performance. Because many of these same activists/artists were going from the streets to rehearsals where they were performing characters very different from themselves, or working with young people in the All Stars Talent Shows, we began to realize that we did not have to just “be ourselves” on the street. That is, we didn’t have to be shy, angry, tired, or whatever. We could also creatively imitate someone else or pretend to be bold, relaxed, or friendly. We could play at who we were becoming. We could make the choice to perform.

Thus the “street work,” over a period of years morphed into the “street performance.” Every street corner where we set up a card table with a poster became a Castillo stage. We began each performance with theatre warm-up games right there on the street. As strangers stepped up to our stage we asked them to improvise a conversation with us, and some, indeed many, did. We began calling each group of street performers an ensemble and each ensemble had a director. While the director performed, s/he also had the responsibility of directing the show throughout the shift.

The street and door-to-door canvasing performances of the 1990s shaped Castillo in three seminal ways. First, they made it possible for the All Stars and Castillo to remain financially independent of government and corporate money. Second, they expanded our community and audience both quantitatively and qualitatively, creating the conditions where ordinary people could participate in building and shaping their own cultural activities and organizations. Third, they reinforced in a concrete, practical way our belief that performance itself can be developmental. Performance became the foundational pedagogy for all of our youth programs and for the free adult classes at UX that grew out of the ASP.

Sheryl Williams leads the community cast of Demonstration 2013 by Dan Friedman, directed by David Nackman at the Castillo Theatre, February 2013. (Photo by Ronald L. Glassman)

This experience also had political/philosophical implications for us. We found that when everyone involved in building Castillo (staff, volunteers, collaborators, donors) was encouraged to perform, especially when these performances were not on orthodox in-the-theatre stages, it cultivated their ability to see themselves as creators and changers of the world. We realized that we weren’t interested in doing theatre in the conventional way. Such theatre may be beautiful, inspirational, provocative, and thought provoking, but in and of itself theatre doesn’t/can’t change social mores or structures. (If it could, we would have had a very different 20th century.) We came to understand theatre as, among other things, a self-perpetuating institution with more or less strict institutional constraints on its creativity. Our understanding of how to make “revolutionary theatre” is to create the community that creates the theatre. That sets up the dynamic wherein people can have a good look at the human capacity for creativity. They are participating in a creative process, and participating in a creative process is what people need, we believe, to see that it is possible for them to bring change and, in practice, to actually make a change.

Part of what that looks like is creating environments in which nonactors are encouraged to perform. Ever since Newman devised and directed Demonstration in 1986, Castillo has worked to maintain a mix of professionally trained and seasoned actors performing along with nontrained performers drawn from its audience, volunteers, and youth programs. Some recent examples: the cast of the 2012 Sally and Tom (The American Way), a musical by Fred Newman and Annie Roboff about Thomas Jefferson and his slave and mistress Sally Hemings, consisted of four musical theatre actors and one performer who had never been onstage before (a woman playing James Madison). Demonstration 2013, a docudrama about progressive mass movements in the United States in the 20th century, had 3 trained actors and 13 community performers ranging in age from 14 to 63. The Donut Play (2014), a love story about an Indian American Dunkin’ Donuts barista and an African American ironworker, had four professional actors and three performers who were Youth Onstage! alumni.

At the same time, Castillo encourages its builders, its volunteers, and its staff to perform as ushers, box office managers, lighting technicians, stagehands, fundraisers, hosts for international guests, and so on. The borders between audience members, actors, and technical and house staffs are fluid, shifting from production to production. Someone you saw onstage in the last show may take your ticket at the next, and be running the light board for a third. People experience creating different performances from different vantages. It’s people creating the theatre and its community that we consider developmental, far more than any particular play or season.

Beyond the theatre itself, the All Stars youth programs are also performance-oriented. Even in the Development School for Youth, which doesn’t involve onstage performance, the task for the young people is to learn the “performance” of the business world.

Although many of Castillo’s productions have employed written scripts, and although roles within Castillo (usher, sound board operator, etc.) are often scripted, an important Castillo through line is improvisation. Performers (whether performing strictly improv or working from a text) need to accept the offers of their fellow performers. To the extent that those offers are indeed accepted and then built upon, something new is created. Further, because improv performance brings into being/incorporates that which does not (yet) exist, it is, by its nature, changing its world by bringing new possibilities into social existence.

This valuing of improv has been most explicitly manifest in the fact that Castillo has, since the early 1990s, maintained a resident improv troupe, The Proverbial Loons being its most recent manifestation. The Loons perform regularly throughout the year. Improv training has been central to Youth Onstage! and for the last four years, the Upright Citizens Brigade, a professional commercial improv troupe in New York City, has, on a voluntary basis, provided free semester-long improv training to Youth Onstage! graduates. Every semester, UX offers an Improv for Everyone course and the New Timers, an improv workshop for people over 55 years of age, both of which consistently remain among the school’s most popular activities.

All of this speaks to what we consider to be the most politically and culturally radical aspect of Castillo: the work we have done to liberate performance from the institutional constraints of the theatre, to bring it into everyday life and put performance to work as an approach to social activism.

“We understand performance very broadly,” Newman said in 1995:

From our point of view performance might have nothing to do with being on the stage. We think you can perform at home, at work, in any social setting [...] With the proper kind of support, people discover that they can, that we can, do things through performance that we never thought we could do [...] In a sense, we’re trying to broaden each person’s notion of “what you’re allowed to do.” (Newman 1995)

Of course, the idea of performance in everyday life is not unique to Castillo. The field of performance studies, emerging during the same decades as Castillo, is premised on performance being a common human activity that permeates virtually all aspects of human social interaction. Erving Goffman famously theorized the performances of everyday life. Allan Kaprow, and many other Happeners and performance artists, also explored, and continue to explore the blurry line between performance as an aesthetic activity and performance as a mundane everyday activity. What is less universally embraced is the connection of performance with development—in all senses of that word—that is, the power of performance to expand the boundaries of “what you’re allowed to do” emotionally, socially, and intellectually.

The All Stars Project national headquarters on West 42nd Street, New York City. (Photo by David Nackman)

While the founders and builders of Castillo and its extended network embraced an activist understanding/practice of performance, we didn’t come to this theory and practice through performance studies. We were unaware of PS until we met Richard Schechner in the early 1990s. Our approach has roots in Marx, and, more specifically, in the early Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who theorized that human beings are collectively cultural and social creators and doers. Vygotsky is the most direct intellectual influence on our performance praxis. Vygotsky, who died in 1934 at the age of 37, studied childhood development. He discovered that children develop and learn through play and by being related to by their caregivers as “a head taller than they are” to do what they don’t yet know how to do (Vygotsky 1978).

In the late 1970s, Lois Holzman, cofounder and director of the East Side Institute, brought Vygotsky’s work to the attention of Newman. Holzman was, at the time, working with Michael Cole, the Rockefeller University lab’s director, who was translating Vygotsky’s writings into English. Vygotsky helped Newman and Holzman see performance as the key to development because when performing (playing) we are both who we are and other than who we are (who we are becoming). They believed his ideas were applicable to Castillo and the All Stars Talent Show Network’s work with adolescents and adults and posited that people of all ages could grow and develop if they were supported to perform “a head taller” than they were. At the same time, we also learned that performance was much more difficult for adults than for babies and children. In 1993, Newman and Holzman, in Lev Vygotsky: Revolutionary Scientist, the first of three books they wrote together, noted a dilemma that Vygotsky never directly grappled with—the fact that although performance was necessary for basic socialization, successful socialization in contemporary American society (and probably other societies as well) extinguished performance. As soon as people learn how to perform in ways appropriate to their gender, class, and ethnicity they are pressured (by the very caretakers who at first encouraged performance) to stop playing/performing. We are told to “act our age,” to “grow up,” to “act like a young lady,” “to stop playing and get to work,” etc. Except for the tiny handful who become professional actors, dancers, musicians, and performance artists, most people stop creatively performing, and hence stop developing, by early adolescence. Even actors are supposed to perform only onstage; offstage their behavior is as prescribed as anyone else’s (Newman and Holzman 1993).

“Yet as we perform our way into cultural and societal adaptation, we also perform our way out of the continuous activity of developing,” Newman and Holzman wrote:

What we (have learned to) do becomes commodified, routinized and rigidified into behavior; we become so skilled at acting out roles that we no longer keep performing. We develop an identity as “this kind of person” who does certain things (and not others). Anything different would not be “true” to “who we are.” (Newman and Holzman 1997:121)

(From left) Homa Hynes, Starshima Trent, Jessica Cooper in Hip-Hop Explosion Workshop, a hip-hop production featuring the text of Explosion of a Memory/Description of a Picture by Heiner Müller. Directed by Madelyn Chapman and Antoine Joyce at the Castillo Theatre, August 2013. (Photo by Ronald L. Glassman)

Performance activism, as we have come to understand it, is the means of reintroducing play and performance as creative social activities in the day-to-day lives of individuals and communities, providing ordinary people with the means of breaking out of prescribed behaviors by creating new relationships, new roles, new emotions, and new ways of developing.

Development is a disputed term used very differently by different people. In the world of nonprofit organizations (known as Non-Government Organizations—NGOs—outside of the United States), the “development person” raises money: the organization’s ability to gather funds is equated with its ability to develop. In the world of political economy, “underdeveloped” nations are agrarian and poor, while “developed” nations are industrial or, increasingly, postindustrial, and rich. In psychology, the prevailing meaning of development derives from the Swiss biologist/psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980). According to Piaget, every child goes through a series of developmental stages linked to biological age. For Piaget, there is a “highest stage” when development becomes fixed, remaining unchanged after that. Similarly, in orthodox Marxist theory, society goes through a series of developmental stages: savagery, barbarism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, communism. What any particular society can achieve is determined by its stage of historical development.

Implicit in both Marx and Piaget is a concept of “progress,” the move from one developmental phase to the next. Hence, in political discourse “progressives” are those who support human development (a label, by the way, embraced by Castillo). The underlying assumption is that development leads from child to adult, from agrarian to industrial, from poor to rich, from exploitation to harmony. Marx and Piaget felt that development was inevitable, the process of both ontology and history. But at Castillo, we don’t assume we know what an “advance” is because our only touchstone for evaluating “advance” lies in already existing social constructs. Our approach to development is not preset, but improvisational. Human societal development seems to us far less scripted, far less predetermined than Piaget and Marx theorized.

Like Castillo’s approach to performance, our understanding of development owes much to Vygotsky who saw human development as a social, cultural process. Development, according to Vygotsky, is not inevitable or fixed biologically or socially. It is something people can (or can fail to) create together. Development is an open-ended, life-long activity. For Castillo, development is a community performance activity. Holzman expresses it this way:

Which picture comes to mind when you hear the phrase “stages of life”? A stepladder or a theatre? If you’re like most people, it’s probably the former or some other step-like image.After all, from the late and great experts on human nature —Freud, Piaget, and Erikson—to their lesser-known contemporaries, researchers have told us that the human life process is best understood as a series of progressively “higher” stages that people pass through. I prefer the theatre image and here’s why. I believe that we human beings create our development—it’s not something that happens to us.And we create it by creating stages on which we can perform our growth. So, to me, developmental stages are like performance spaces that we can set up anywhere—at home, school, the workplace, all over. (Holzman 1997:33)

We create these performance spaces just as we create the performances that take place in them. Castillo is conceived as and self-consciously built one of these “performances spaces.”

Development, as Castillo enacts it, is not predetermined by ideology, religion, science, or any other script, but is created continuously by our shared improvisational activities. Building the “stages”—in all meanings of that word—for performing development is what Castillo, the All Stars, and other activities influenced by them, do.