Creating a Public Space/Activity for Civic Engagement and Development

Dan Friedman, Associate Dean, UX

Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities Conference 2017

“Arts in the Public Sphere: Civility, Advocacy and Engagement” Northeastern University

November 3, 2017

[+download] In one sense my talk this morning has nothing to do with the concerns of the Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities. It is not at all about “fostering and championing the arts in higher education.” This, of course, is a valuable concern and an important mission. It’s just that my reflections this morning have nothing to do with research universities or, for that matter, with higher education. I’ve come, instead, to share the experience of a grassroots school that is primarily being built by and for working class adults of color in New York City.

Unlike my fellow panelists, what I’m talking about is not so much a public space, although it takes place, for the most part in a beautiful performing arts and development center on 42nd Street in Manhattan with three stages, rehearsal and classrooms.

That’s the sidewalk outside the building during a typical evening. However, rather than focusing on it as a physical space, I want to talk about this school primarily as a social space, or perhaps more accurately, a social activity that is coming-into-being through the efforts of those who use it.

This school is free, has no grades, and offers no degrees or certificates. Students don’t come with the expectation of getting vocational skills or job training; they take courses and go on cultural outings together because the subject interests them, or simply to be exposed to new experiences, new ideas and new people. It’s been around for seven years and has had slightly over 7,000 distinct students.

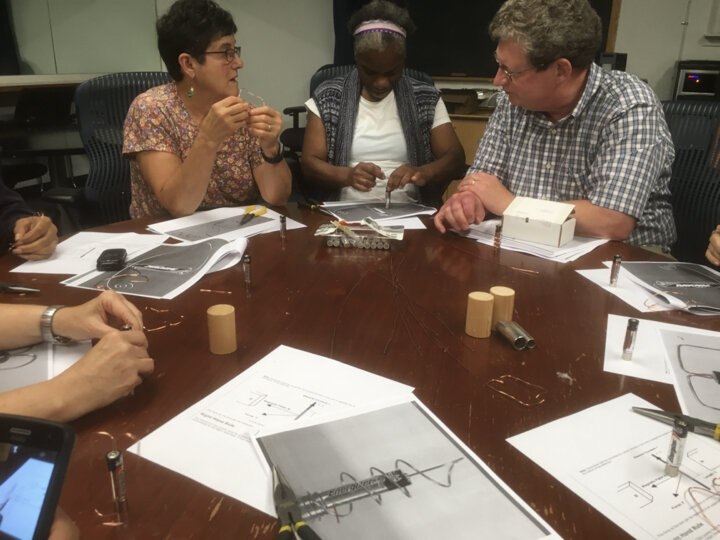

Participation in this school has no prerequisites. Students in a class may have a Ph.D. or may not have finished high school. Some classes have 7 year-olds learning together with 87-year-olds.

The classes are all taught by volunteers, experts in the subject they are teaching, but not necessarily formally trained scholars or teachers. Classes and workshops have been taught by everyone from: hip-hop pioneer Grand Master Flash to Hugh Ryan Mackey, a Toni Award Winning Broadway producer; bank and hedge fund executives; professional actors, dancers, and clowns; fashion designers and make-up artists; African drummers and beat box virtuosos; screen writers and film makers; psychiatrists and psychologists; public relations executives; attorneys and community activists; retired high school teachers and social workers; as well as people with doctorates in everything from physics and biology to Latin American history.

Another feature of this school is its development coach operation. UX development coaches are most often well-to-do, well-educated, and culturally sophisticated professionals, organized and trained by Dr. Lenora Fulani, a developmental psychologist and long-time community activist, who serves as the school’s dean. They do short coaching sessions with UX students at the beginning of each semester. In those sessions, they talk about the student’s hopes and dreams and the students are encouraged to discuss things they’d like to try that they’ve never done. Then, a week for two after this conversation, the coaches take the group of individuals they talked with on free cultural outings to museums, concerts, parks or galleries around the city.

As I think is obvious from even this minimal description, the practice of this school doesn’t relate to the vertical hierarchy embedded in the phrase “higher education.” Its compass is, rather, horizontal—generating an ever “broader” and “deeper” (as distinct from “lower” or “higher”) education.

At the same time, my talk has everything to do with the theme of this conference: “Arts (and, I would add, science) in the Public Sphere: Civility, Advocacy and Engagement.” The experience of the grassroots school I’ll be talking about, is, to a large extent, the experience of creating a new, dynamic public sphere in which ordinary working class people are building an activity and an environment for themselves and their communities in which they can learn, develop, discover and create their civility, advocate for themselves, engage in new ways with not only with their own communities, but also with people from other cultural backgrounds and social strata. In the process, they are generating what might best be called a culture of active curiosity and citizenship.

*

The name of this school is UX. Its original name was University X but our attorney told us that we couldn’t call ourselves a university unless we were certified by the State of New York. Since we didn’t want (and wouldn’t have gotten) state certification, we were glad to drop the word and embrace an odd name consisting of only two letters—UX. When asked, we explain that the “U” indicates that we are a university-like school of continuing development and that the “X” stands for the Unknown. Why the Unknown? Because the content, the form, and the outcomes of UX are all unknown and unknowable in advance. To a large extent, UX is being improvised by those participating in it, a method that allows for multiple inputs and maximum creativity—along with minimal “knowability.”

Photo: Ronald L. Glassman

The dean of UX, as I mentioned, is Dr. Lenora Fulani. Fulani is a developmental psychologist, community organizer and progressive political activist in New York City with a national reputation as a radically progressive grassroots educator and political independent. In 1988 she became the first African American and the first woman to be on the presidential ballot in all 50 states—and she did it as an independent! The rapid growth of UX since its founding in 2010 would not have been possible without her connections to and reputation in the poor communities of New York City. I’m the associate dean of UX. I’ve been a progressive political activist and a participant in socially-engaged, community-based and experimental theatre since I was a teenager. I have doctorate in theatre history and am a founder and the artistic director of the Castillo Theatre, a 35-year-old theatre in New York City. Fulani and I have worked together on various cultural and community organizing projects for more than three decades. What I’m sharing with you today is, therefore, not an objective, scholarly account of a social and educational experiment, it’s a passionate report from someone deeply invested in the work.

*

How is this social and educational experiment made possible? First of all because UX is not a stand-alone project. It grows out of and is part of a four decade-long history of community organizing and institution building based in New York’s poor communities. In particular, UX has grown out of the All Stars Project, a 35-year-old national nonprofit organization that helps young people and adults in poor communities to have experiences that are growthful and developmental. Headquartered in New York City, and active in five other U.S. cities, its stated mission is “to transform the lives of youth and poor communities, using the developmental power of performance, in partnership with caring adults.”

That phrase, “the developmental power of performance,” is key to the work of the All Stars and UX. Play and performance are at the core of the All Stars’ approach to youth and community education and development. The All Stars’ working definition of performance is that it’s the human capacity to simultaneously be who-you-are and who-you-are-not, or, put another way, who-you-are-becoming. In the tension/energy/space between who-we-are and who-we-are-not, we can, and do, make all sorts of creative discoveries about ourselves and others. Performance, we have come to believe, gives us the ability (and the license) to try out new emotions, new ideas, new relationships — in short, new possibilities.

Further, performance is not, in our experience, primarily cognitive; it is cognitive and physical, reflective and emotional all at the same time. We have thus come to believe that the most fruitful approach to engaging social problems is not principally through ideas — “each one, teach one” — but through performing new possibilities with constantly changing/evolving ensembles. The more diverse the social ensemble, we have found, the wider the range of possibilities generated. One of those diverse ensembles is UX and while the content and form of its courses vary tremendously, all our teachers and students approach their subjects playfully and with the assumption that they can develop by performing beyond themselves—that is, performing as students and teachers, as scientists, artists, historians, etc.

The All Stars Project was founded in 1981 by Fulani and the late Dr. Fred Newman, a Stanford trained analytical philosopher turned community organizer. For over 40 years Newman provided intellectual and creative leadership to the All Stars and an extended network of community-based organizations and activities of which the All Stars is a part. The All Stars Project is led Gabrielle L. Kurlander, who has been president and CEO since 1990, leading it from a small grassroots community organization to a national non-profit with an annual budget of $10 million with 65 full- and part-time employees and over 900 people who volunteer with it annually.

In addition to UX, All Stars programs include: the All Stars Talent Show Network through which young people perform in and produce neighborhood hip-hop talent shows; Youth Onstage!, which gives young people access to free training in the performing arts under the direction of volunteer theatre professionals; the Development School for Youth which partners with the business community to help young people create a professional performance; Operation Conversation: Cops and Kids, a partnership with the New York Police Department that brings young people from poor communities together with police officers in performance workshops where they learn to listen to one another and create a new kind of relationship. The All Stars Project also includes the aforementioned Castillo Theatre, which started as a separate institution and joined the All Stars family in the late 1990s.

Photo: Ronald L. Glassman

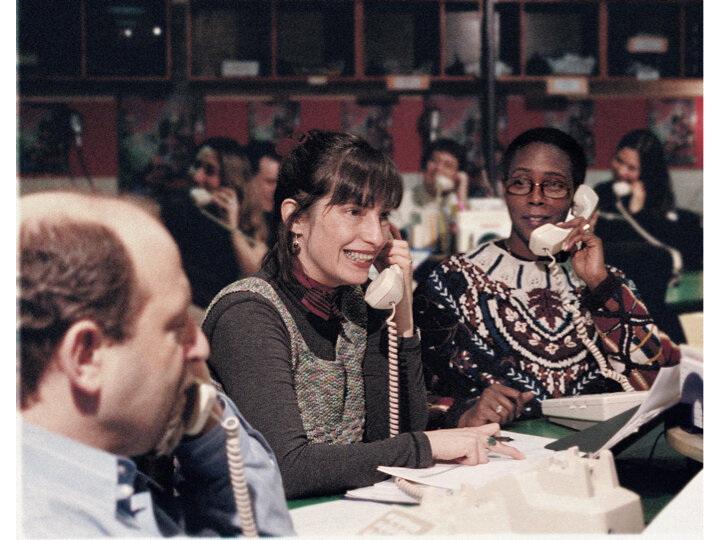

The second thing that makes UX, and all its sister programs, possible is that the All Stars is 100% privately funded. It has never taken government funding nor depended on corporate foundations, which has allowed it to be flexible, to constantly experiment, and to be answerable first and foremost to those who it serves. In the early days of the All Stars, its volunteers raised all its money on the streets of New York. We were all volunteers then, raising money after work and on weekends. At the height of this street operation, we had up to seven teams deployed to various parts of the city every Saturday and Sunday, and had a door-to-door canvasing operation as well. In the early days, people we met might give us a dollar or five or ten. However, when you’re on the street that much in New York City, you also meet rich people.

Today, there are individuals who regularly donate tens of thousands of dollars to the All Stars. The give on the terms of the All Stars, in support of its methodology and programs, and donors are consistently being organized to not only give money but to become involved in building the programs as well—as UX teachers and development coaches, as hosts for visits for the young people in the Development School for Youth, as house staff and tech operators for the Castillo Theatre and much more. Thus they are impacted on by the All Stars activities and programs in a much deeper way than they would be by simply giving money, and through their active participation they get to impact on the All Stars as well. The All Stars calls this organizing activity “participatory philanthropy.” I also should note that the fund raising never stops and that the All Stars never becomes dependent on one individual or group of individuals.

I can’t overstate how essential this independent funding is to the creativity of the All Stars Project. It allows the All Stars to minimize bureaucracy and maximize flexibility. Free of the authority of the state, corporations or universities, All Stars has been able to constantly revamp its activities and spin off new projects driven only by what works for and appeals to those it is serving.

UX is a direct result of that freedom and flexibility. For much of the last 30 years, the All Stars Project concentrated on building free, performance-based after-school development programs with young people from poor communities. Repeatedly over the years, parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles and the older siblings of young people involved in All Stars programs would, say things like: “I don’t know what you did with my kid, but he wants to live again;” or, “I wish I had found the All Stars when I was young.” There was clearly a hunger to learn and develop in the poor communities, so in 2010, given that we were not beholding to government, foundation or university bureaucrats, we decided to see if people in the communities of New York were willing and able to generate an activity, build an organization, create an environment, to promote that learning and development. They were—and they went on to build not just a school, but also new sphere of civic engagement and advocacy.

*

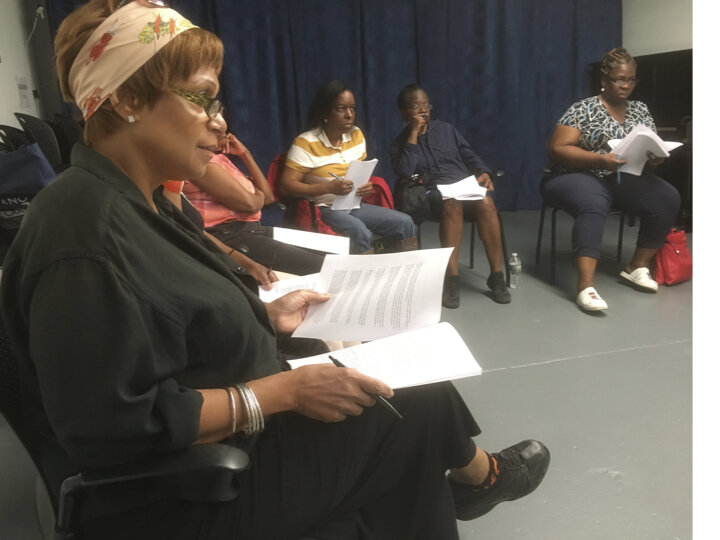

To understand UX as the creation of a new kind of public space and activity for civic engagement and development, the key thing to grasp is that its thousands of students and hundreds of teachers and coaches are volunteers. They all donate their time, energy and skills to bringing the school into existence. It helps, of course, that the All Stars provides space, rent-free, for the classes at the 31,000 square foot performing arts and development center on 42nd Street, near Times Square. However, all the space in the world would mean very little without the self-organizing of the UX students and teachers. Student volunteers produce the classes and the development coach trainings. They run the tech for the teachers, input student data into the UX data base, go out the streets and get on the phones to organize hundreds of people to attend the Opening Day event that marks the beginning of each trimester. Perhaps most vitally, UX student volunteers get together every Tuesday evening and Saturday morning and call other students to remind them of upcoming classes that they’ve registered for. Seven thousand students don’t just show up; they’re organized to do so by their fellow students.

When students talk about their experience at UX they talk about the impact of the classes, the value of being exposed to new kinds of people and cultural activities, and, most relevant to our conversation here, they also speak of the growth that comes from building the school together with people from diverse backgrounds. Velma Freeman, an African American woman in her sixties put it this way:

“My development coach, Lisa, took us to the American Museum of National History and I brought my granddaughter along. I took the Black History as American History course and I learned a lot more about slavery and the Civil War. I took the poetry class and discovered that I could write poetry! I also went on the All Stars bus to see an All Stars Talent Show and it was great to see children from all over the city performing and having so much fun. Since I started coming to UX I’ve also seen two plays at the Castillo Theatre—The Fabulous Miss Marie and Dr. DuBois and Miss Ovington—and I enjoyed both of them.

One of the things I like most about UX is how Dr. Fulani brings rich and poor people together. They get to know more about our lives and what we have to go through and we get experience some of the things they take for granted. Right now I’m homeless and going through some tough times with my family. Despite what I’m going through, I look forward to coming here to be happy. Why should I stay away and be depressed, when I can grow so much through my involvement with UX?” (Velma Freeman, remarks for UX Opening Day program, June 21, 2014)

Here’s Bernadene Weekes, a retired office manager for a construction firm:

“First of all, it’s very educational. In one class I learned the history of New York City. In another I learned how to get my finances together. I learned about our grand jury and justice system in a class taught by two leading civil rights attorneys. I took a class in “Acting for Everyone” and another in “Public Speaking,” which is helping me in talking to people on the street when I do UX street outreach. …

“UX is also culturally developmental. We’re afforded the opportunity to attend plays at the Castillo Theatre, poetry recitals by UX students, visiting dancers from Brazil, and a lot more. … Just meeting and socializing with the wide variety of people you meet … raises the quality of my life.

“I’ve also been able to contribute my skills to the building of UX. I worked for many years as an administrative office professional and now, as a UX volunteer, I use those skills to help … produce the UX Opening Day Development Coaching Operation. This it gives me something positive to fill my days and helps me keep my skills active and sharp.” (Bernadene Weekes, remarks at the “After School City” fundraising reception, June 2, 2015)

Theresa Chaney, who spent most of her life as a hospital worker, says of herself, “Growing up on the lower east side of Manhattan was tough. The poverty, crime and lack of resources – especially in our schools - did not nurture me or support my dreams. I have had good jobs and have been able to live comfortably in my adult life but the effects of poverty are hard to break. I have always struggled to fit in and always felt rejected by society. And I had been blaming myself and beating up on myself for feeling this way. That all changed when I walked through the doors here [at UX].” Theresa has been a student and volunteer with UX since its first semester in the fall of 2010. Along with the classes and cultural events, she cites her work as a volunteer builder of UX as key element in her development:

“As a part of our UX phone room team, I talk with so many different members of our bigger community - from other volunteer organizers to fundraisers to youth in our programs before, after and during the organizing shifts. These conversations ‘in the cracks’ are a big part of my development. Along with my UX classes and my work as a leader organizing for UX, I have been inspired to attend Borough of Manhattan Community College, where I organized an advocacy group for senior students and am now pursuing a one-year pilot nursing program. (Theresa Chaney, remarks at the “After School City” fundraising reception, June 13, 2016)

Like Theresa, who returned to formal “higher” education and organized an advocacy group for senior students at her community college, other UX students have used the experience of being a student and a volunteer at UX to build things in other parts of their lives. Rakeen Dow and Jessica Maeti, who met in a UX poetry class, went on to form the Living Poets Society that has been organizing poetry readings in churches around New York for two years now. However, most UX students are not necessarily building new organizations as much as bringing a development attitude into their daily lives. Viani Edwards, who came to UX after joining the All Stars Youth Onstage! program, put it this way in 2014, when she was 18 years old:

“This year I had the opportunity to speak at two conferences with Dr. Fulani, one in Dallas and the other in Philadelphia. I voiced my opinion on matters that were quite serious. At these conferences and when I was a UX youth development coach trainer, I got the opportunity to teach adults and have them listen to me wholeheartedly. Having these experiences, I learned to approach life differently, in a way that would not only benefit me but the people I come into contact with. I carried what I learned everywhere and I started to have an impact on the people around me. My mom saw me reading a book called Let's Develop! by the late Dr. Fred Newman, who, with Dr. Fulani, founded the All Stars Project, and she asked me if she could ‘borrow’ it. I haven't seen the book since. I find myself having discussions with teachers about development. I even wrote a poem about development and won an award. For the first time in my life people have actually started to listen to the things I have to say and people think that I’m smart.” (Viani Edwards, remarks for UX Opening Day program, June 21, 2014)

Mary Hall a 68-year-old grandmother from Harlem, says, “I have been able to bring what I have learned to my family. I especially love sharing this with my ten-year-old granddaughter. I bring her to a lot of the UX events. She’s exposed to live theater, taking classes, and going on field trips in New York City.” (Mary Hall, UX Opening Day remarks, October 8, 2016)

Another result of building UX, for some, is in developing a sense of being part of and taking responsibility for a bigger world. Janetta King, an 17-year-old high school student, put it this way, “My time here is a big deal because I live in a poor community and there’s a lot of anger and violence. It’s easy where I live to get stuck without hope. What goes on here is so different than my school and my neighborhood because at UX people care about me and my development. And I’ve had the chance to try new things. I never would have been in plays or traveled to conferences in other cities—these are things I didn’t even think about a year ago!” (Janetta King, remarks at Fulani Reception, April 11, 2014).

The connection between the All Stars and UX’s approach to performing, development and civic engagement is not lost on the students. Rakeen Dow, put it this way:

“It [My experience at UX] has enabled me to come to the realization of my socio-economic status as a Black man and a poor person in a society that stigmatizes poverty. … I’ve come to understand that poor people have to ‘perform’ and not ‘conform.’ Without performance we’ll be trapped by the labels society has imposed on us.

“Most importantly, I have come to embrace the message that Dr. Fulani and the staff of UX convey in regard to performance—that it’s essential that I, as well all other members of UX, the All Stars and the community, have to play an active role in eradicating the injustices that are confronting the poor worldwide.

In sum, I would like to quote William Shakespeare, “All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” That is so true. However, what Shakespeare leaves out and what Dr. Fulani brings in is the question: Are you going to play an active role in the performance? Or are you merely going to be a prop used by others to create the scenery? We need to become actively involved in creating the new performances to facilitate the changes that need to take place on a national and international scope.” (Rakeen Dow, remarks for UX Opening Day program, September 27, 2015)

This sense of civic responsibility among UX students is reflected in the emergence over the last few years of a new organization called the Committee for Independent Community Action (CICA). It was initially made up of UX students who wanted to work with Dean Fulani, who has been a respected independent community leader for 40 years, to engage political and economic issues confronting the poor in New York. When the Committee for Independent Community Action began to challenge the ongoing attempts to privatize some of New York’s City’s publically owned, subsidized housing for the poor, its numbers grew rapidly. Gwen Dow-Chance, a pre-school teacher says, “One highlight [of my UX experience] was marching in the Harlem Day Parade in the UX contingent in opposition to attempts to privatize some our public housing.” (Gwen-Dow Chance, UX Opening Day remarks, October 8, 2016), and Mary Hall adds that, “Working on gathering signatures to prevent the privatization of New York City Housing Authority housing for low-income families has increased my desire to make a change.” (Hall 2016)

The New Timers, which is an ongoing UX improv workshop for people over 55 years-of-age, has recently devised a play called The Stoop which, inspired by the organizing work of the Committee for Independent Community Action, looks at the conflicts sparked by gentrification in New York’s poor neighborhoods of color. In addition to having performed it twice at UX, the New Timers have begun touring the play to churches and community centers around the city.

Just as UX emerged from the All Stars Project in response to a want/need in the city’s poor communities of color, the creative dynamic sparked by UX is now generating new projects, initiatives, and performances. With no financial or bureaucratic “higher-ups” to answer to, the radically democratic process of trying new things and, if they work, building with them, is continuing at an accelerated pace at UX.

*

As these examples, I hope, illustrate, the activity of organizing and sustaining grassroots organizations such as UX results in the builders developing themselves and each other. There’s something very special about belonging to group that you are a part of creating, that didn’t exist before, that got built through you and others working and playing together. You not only have the group you’ve created, you also have new kinds of relationships with you fellow builders, relationships nurtured and supported by the very organization, the community, you’ve built. Put another way, the building of such organizations is simultaneously a tool for generating citizenship culture and the result of that culture being generated.

UX is something new, at least in the United States. It is, I believe, a new civic realm, an activity and organization that is allowing thousands of mostly poor people of color to create their own development. It’s not a university or a museum or an arts center. In some ways it’s all of those. In another way, as I hope I’ve made clear, UX is something qualitatively other than any of those. What makes it “other” is who is building it and how they’re doing the building. “Ordinary” working class people are using the method of play and performance to build something for themselves and their communities, and they are doing it by building relationships with well-to-do donors, with intellectuals and with artists. Together this unusual social and financial alliance has created a new kind of space for civic engagement and development.